1880s & 1890s

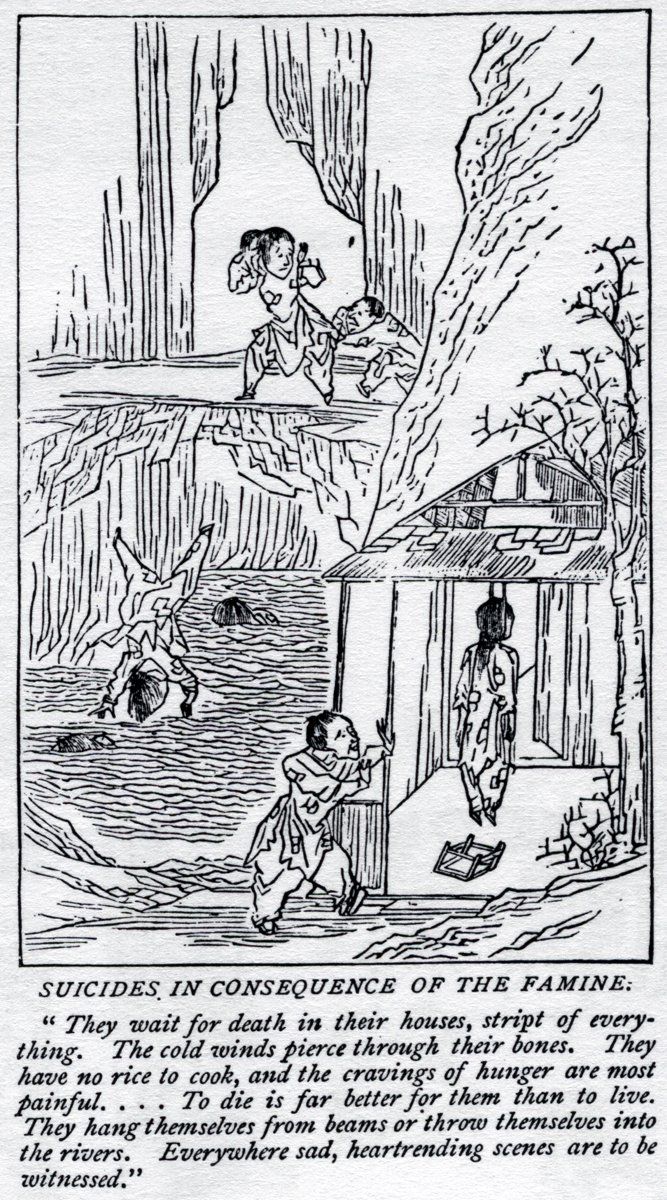

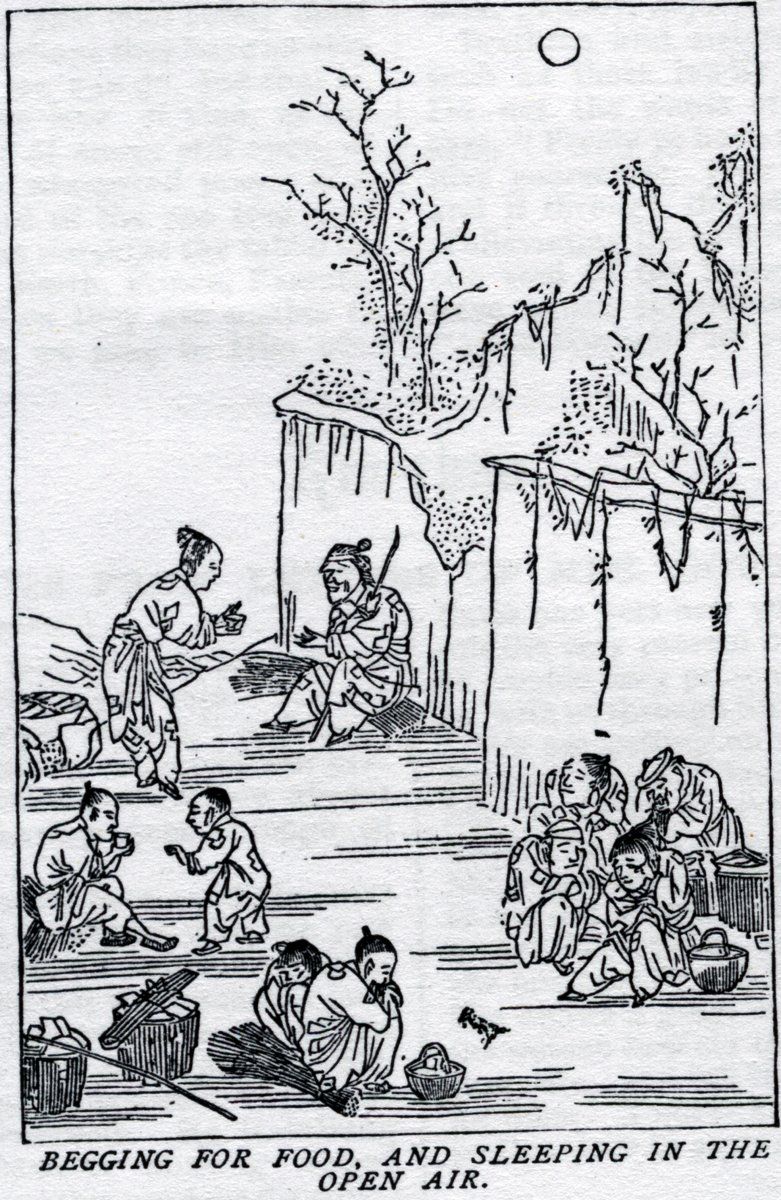

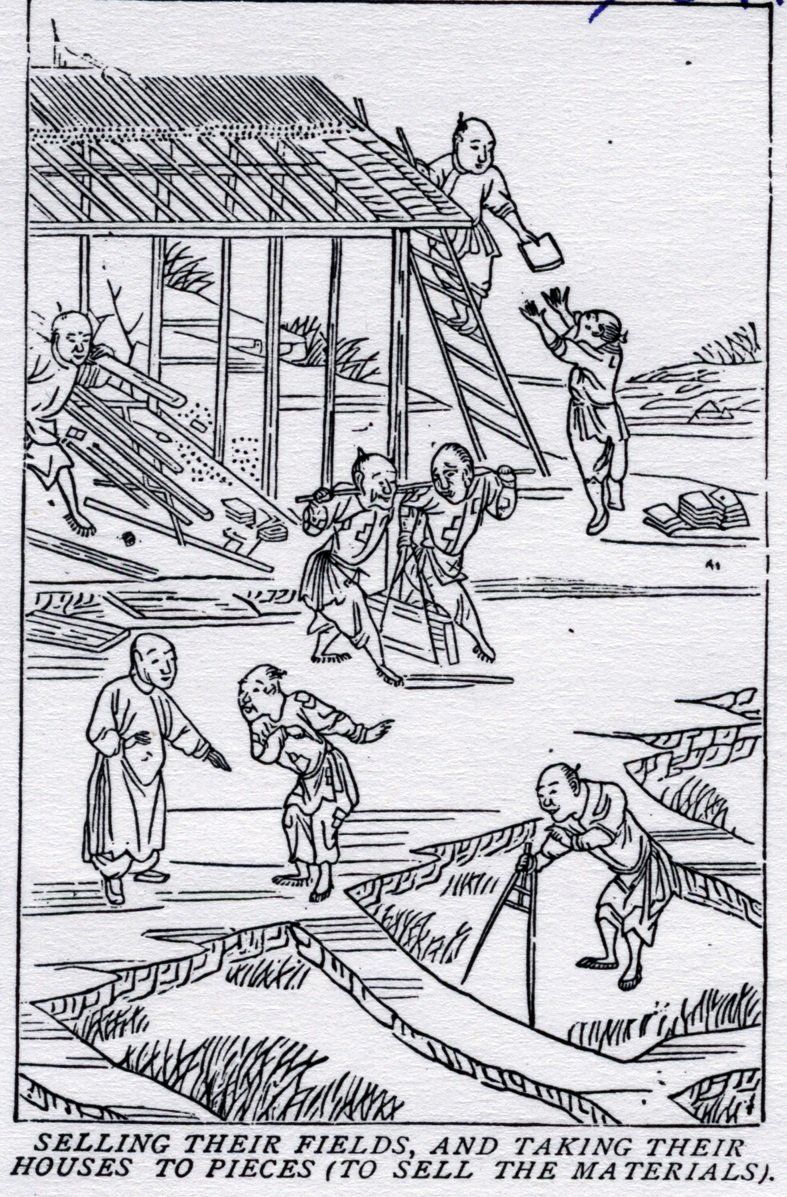

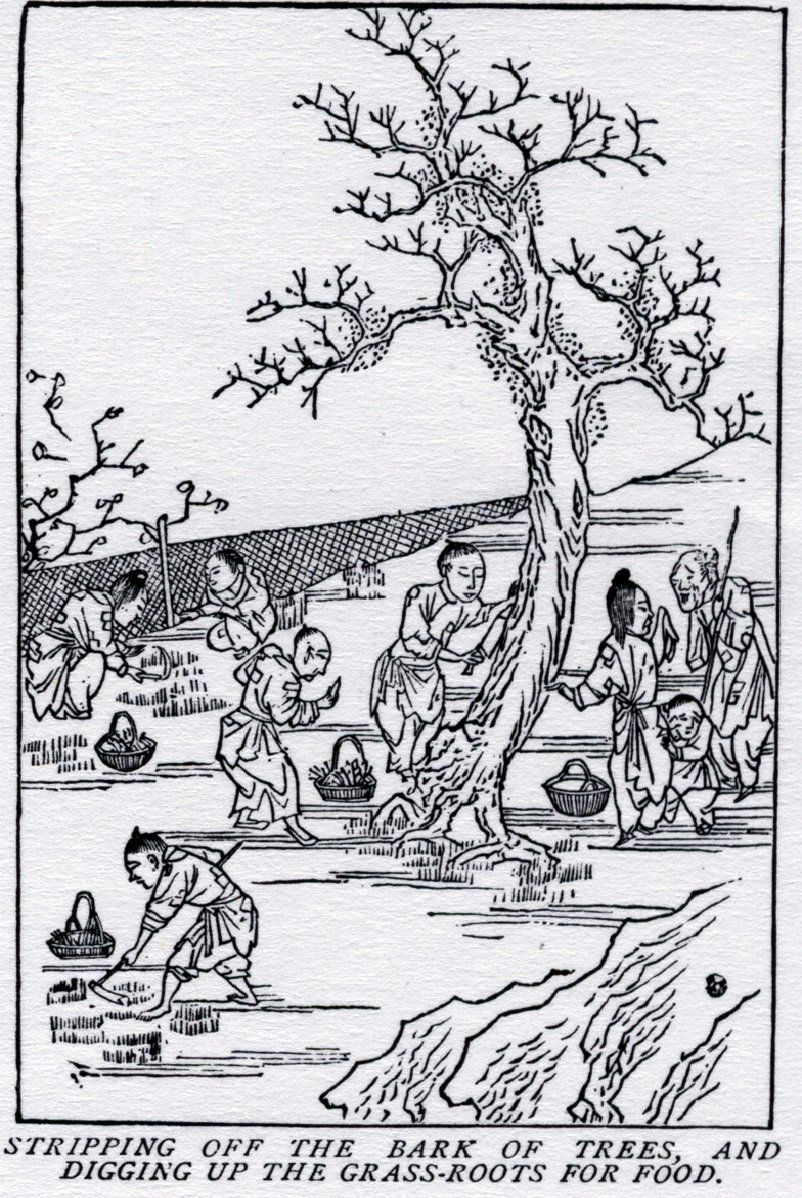

A series of sketches from the 'China's Millions' magazine, depicting the severe famine that blighted the people of Shandong in the 1870s and 1880s.

After two decades of Evangelical endeavor, missionaries in Shandong were a fractured and bruised lot as they entered the new decade of the 1880s. One magazine summarized their efforts by saying,

"During the 20 years ending with 1880, there have been in all 98 resident missionaries in Shandong. Of this number 49 were women... 15 missionaries have died, and 43 from failure of health or other causes have left the field. Twenty-five either died or left the field within one year after arrival, and 19 others did not remain beyond two years." 1

At the dawn of the new decade Evangelical churches in Shandong numbered a little more than 1,000 converts, whereas the Catholics boasted 72,838 adherents in 471 churches throughout the province. 2 The ratio of believers was about to draw much closer, however, as Jesus Christ established His church among those who desired to obey His teachings.

In 1885, just five years after reporting approximately 1,000 Chinese Evangelicals in Shandong, things had improved to such an extent that the Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal reported, "There are 39 Protestant missionaries in the province, and nearly 5,000 native church members, which is about one-fifth of all the members in China." 3

God's Precious Gems

Mrs. Li of Penglai. When asked if she was ashamed of Jesus, she replied, 'Ashamed of Jesus?

I should like to wear a Christian badge on top of my hat so that all might know I am a Christian!'

As the decade progressed, exciting reports of conversions and healings began to flow much more regularly from the pens of Evangelical missionaries, who were eager to share news of breakthroughs in their work with the rest of the Christian world.

In the mid-1880s, a CIM worker, Miss Fosbery, joyfully shared about a teenage boy who gave his life to Christ:

"Soon after I arrived in Yantai a boy named Shu-nga was brought to the hospital. He had a disease in his knees and could not walk.... Every morning I went into the hospital to bandage his poor thin legs.... After a time we put his legs into plaster, and this seemed to do him good. He gradually got better, for we took care of him, and fed him well through the cold weather. But one day, when he was feeling better, he went outside and stayed a long time in the damp, and this brought on the inflammation in his knees again, and he became very ill. He got worse and worse, and we all thought he would die, and he could scarcely swallow anything....

At night we used to kneel by his bed, and ask God to make him better. By-and-by he improved, and as the warm weather came on I had him come to the house so that I might teach him to read. Every day he listened to the preaching in the chapel, and gradually understood about the Lord Jesus. One day I asked him if he believed, and he said, 'Yes,' and that he prayed every day to the Heavenly Father....

About a month ago he was baptized and received into the Church as a follower of Jesus. He has no parents, and his only brother is very poor, and has a good many children of his own to keep.... He is a nice bright boy, with large dark eyes that sparkle as he talks. He is about 15 years old." 4

CIM workers shared more testimonies of Chinese coming to faith in Jesus Christ. One account said,

"Recently my teacher's wife was accompanied here [Ninghai] by her brother-in-law, who remained only two days. At one evening meeting his brother, my teacher, broke down in prayer, sobbing aloud, for the conversion of his relatives. His younger brother was evidently moved. I asked him if he would like to trust Jesus and be saved. He said he would.

We knelt down together, he with tears in his eyes, and he prayed, I suppose for the first time in his life, and I believe the Lord saved him. This is the fourth from that family who has trusted the Savior since we came here, and we are expecting more of them to be saved soon.

I had a letter recently from my teacher's father, lately baptized. He says he gets persecuted, but then he opens the New Testament, and always gets joy and comfort from that. " 5

The decade concluded with another encouraging report from Shandong:

"If others could see the sights that daily meet our eyes, I think their hearts would be moved to pity. Twelve persons have been baptized during the last year. One of the first three women baptized was an old lady of 84-years of age. It seems as if God had kept her alive to hear the gospel. The first time she heard she seemed to understand more than most of them do, and weak, and old, and ignorant as she was, she seemed to take in the love of Christ. One day she asked, 'Do you really believe Jesus loves me?'

On another day she told me, 'Ah, my life has been all bitterness and sorrow. I have never known happiness since I was eight years-old, when my parents died.' I said to her, 'Now you know and trust Jesus, He will care for you, and soon you will go to live with Him, and then it will be happiness for evermore.' Her face brightened, and she replied, 'Ah yes, and when I get to heaven I shall look out for you to come.' The poor old thing soon died of cholera." 6

After an estimated 15 million people starved to death during the 1877 famine, 7 the population had only just recovered when a second severe famine struck Shandong in 1889. Regular missionary work of the mission was again set aside as all effort focused on providing aid to the starving population. Once again the Church in Shandong grew rapidly, with the number of Evangelical Christians more than doubling from 1,020 to 2,315 in four years. 8

As the 1880s drew to a close, the Church in Shandong looked back on a decade of steady growth. The number of Evangelical Christians in Shandong appears to have quadrupled during the 1880s. Although the Body of Christ was still miniscule compared to the overall population of the province, a faithful remnant had been established in many parts of Shandong which would prove to be the first-fruits of a great later harvest.

The opening ceremony of the Jinan Christian Hospital, attended by the Governor of Shandong and dignitaries in 1889.

Colonial Expansion

Shandong Province was a valuable prize to foreign governments because of its rich mineral deposits and its deep-water ports. A three-way war between China, Britain, and France in the early 1870s resulted in the British seizing the strategic port town of Yantai (formerly Chefoo).

The German government also had imperialistic designs on the province, and the tragic martyrdom of two young German Catholic missionaries in 1897 gave them an opportunity to plant their flag in the rich Shandong soil.

Germany retaliated for the murders of Nies and Henle by invading the city of Jiaozhou with a fleet of warships. They demanded the removal of the Governor of Shandong, and used the martyrdoms to seize Qingdao. In the process,

“Germany obtained a 99-year lease, as well as the right to secure mining and railways concessions in Shandong. The German action precipitated a scramble for land by other countries. Russia obtained a lease on Lushun (Port Arthur) and Dalian, while Britain secured a lease on Weihai and the New Territories opposite Hong Kong.... By the close of the nineteenth century, there was a real prospect that foreign governments would shortly control many strategic provinces and eastern ports.” 9

Partly because of the opportunities afforded them by the wave of colonial expansion, the number of foreign missionaries in Shandong Province grew markedly throughout the 1890s, although for much of the decade the missionaries appeared to have spent their time forming an effective mission philosophy among its members. Many detailed discussions were held as the mission force tried to work out the most effective way to propagate the gospel in Shandong, and throughout China in general.

A group of missionaries at Yantai, 1891.

The discussions included widely disparate views on the benefits and pitfalls of supporting native evangelists; and much ink was spent arguing the pros and cons of humanitarian work in response to the regular floods and famines that blighted the people of Shandong. As today, some missionaries just wanted to proclaim the gospel and considered humanitarian assistance a compromise, while others saw it as a tremendous opportunity to display the love of Christ to the poor and oppressed, in the hope it would lift many out of bondage and into the Body of Christ.

Alfred Jones, a British Baptist, was one missionary who challenged the prevailing mindset of the day with his thoughts on how to alleviate poverty among the masses of Shandong. In 1894 he wrote,

"Poverty is itself a great evil, because it directly causes great actual suffering. Poverty impels to covetousness and aids vice and crime.... Do not be deceived in approving of others being poor and not loving it for yourself. Moreover, to relieve poverty is not to make men rich. True, more of the poor believe the gospel than the rich, but the point is, still more would do so if not poor.

Again, some missionaries seem to look on philanthropy as if it were bait on the gospel hook. I fear missions do some things as if only to get natives to believe Christianity and enter their church. God sees such things through and through. Outwardly they look like virtue. The act is the same; inwardly there is no virtue in them." 10

A Bold Prediction

Although missionaries and their Chinese converts continued to receive a rough reception in many parts of Shandong, the Spirit of God continued to move in the hearts of many people through the written Word. The Chinese Religious Tract Society was founded in the late 1870s, and zealously distributed tons of Bibles, gospels and evangelistic tracts throughout the country each year. This approach yielded much fruit, with one report detailing,

"The Chinese are a reading people, and there is every reason for operating through books on the Chinese mind. They have had an unbroken succession of writers since the days of Confucius....

In the course of missionary journeys in Shandong I found that the practice of reading aloud exists in families, and that the women of the family sit and listen with interest. As long as the supply of oil lasts, the reading continues. The women like to be read to while working with their hands at some useful kind of needle work.... The reader may be a youth of the family or some woman who can read. She may belong to the family or she may be hired." 11

As the good news of Jesus Christ continued to spread throughout the towns and villages of Shandong, an increasing number of people put away their idols and dedicated their lives to the Living God. The missionaries were careful to teach that the local believers must finance their own church buildings, schools and workers, lest they fall into the pit of dependency upon foreign funds. The tireless Hunter Corbett detailed some of the exciting growth in this 1890 report:

"During a journey of two months in the interior, visiting churches, stations and schools, 40 people were received into the church on profession of faith, making 92 this year. Three church buildings were dedicated. Two of them are built of stone and the other of brick. These buildings cost the Christians no small amount of self-denial. Not a few, who were unable to give money, paid their subscriptions by wheeling stone, brick, timber, attending masons, etc.

A number not connected with the church contributed labor. They said the Christians were good neighbors who helped others and consequently deserved help in return.

Our school work is extending rapidly and proving a power in dispelling darkness and extending a knowledge of Christianity. Children and grandchildren, by repeating in their homes Bible stories, hymns and truth learned in Christian schools, have awakened a desire on the part of parents and others to learn more, and have led not a few to accept Christ as their personal Savior....

During the year about 500 adult members have been added to the Church in Shandong. More than 1,000 others were reported as observing the Sabbath, earnestly studying the truth and desiring baptism....

The present outlook in this province compared with 25 years ago, when there were no converts but only prejudice and opposition on every hand, is surely encouraging. Surely there will be mighty changes all over China, and multitudes led to accept the truths before another 25 years pass." 12

Some of the Shandong missionaries were so encouraged by progress in the 1890s that one even boldly predicted, "If the present rate of progress is maintained in Shandong, the province will be Christian in the next 50 years." 13

Problems in the Church

Despite such optimistic forecasts, many problems continued to plague the fledgling Shandong Church throughout the 1890s. Vicious groups of bandits roamed the countryside, inflicting untold misery on the population and stunting the growth of Christianity.

With China on the verge of total lawlessness and powerful warlords holding sway over vast areas, many of the missionaries and Chinese leaders felt like the kingdom of God was struggling to survive, with each step forward being met with strong resistance.

In addition to the outward hostilities, many Shandong Christians came face to face with important moral and ethical questions, as they sought how to follow Jesus Christ as devoted disciples in the midst of communities saturated with idolatrous practices and superstitions.

One of the major points of contention for Chinese Christians was the question of involvement in ancestral rites. Many generations of family lineage had created a deep-rooted sense of community and belonging among the clans and families of Shandong. Ancestors were venerated, and numerous complex rituals required the whole community to participate in festivals, funerals, and other special occasions.

Shandong believers who had personally experienced the saving grace of the Lord Jesus, however, struggled to justify how a Christian could be involved with ancestor worship in any way. While they wished to remain part of their communities and sought to reach their families and relatives with the love of God, many found the rituals of ancestor worship incompatible with the teachings of the Bible.

Predictably, as soon as Chinese Christians took a stance that went against the popular grain of their communities, persecution arose. First, believers were placed under intense pressure to observe the customs, and were warned that to step out of line would bring disgrace upon their dead ancestors and calamity would afflict their communities because the spirits would be offended.

Persecution increased on Christians who refused to budge. Many believers were beaten and expelled from their villages. In various parts of the province small clusters of ostracized Christians emerged, seeking one another's help as they faced life with no family support but the family of God. Family leaders often expressed their disgust at the stance of Christians by holding funeral processions, symbolizing that the Christians were dead to them and were no longer welcome in their communities. Some church-goers cracked under the intense peer pressure, renouncing their faith in Christ.

Disciples of Christ living in the cities tended to survive more easily as they could melt into the population and seek employment. Those in the rural areas of Shandong, however, found things more difficult and many suffered terribly because of their faith in the Living God. In some cases, the village leaders grew so infuriated by the believers' refusal to venerate the dead souls of their ancestors that Christians ended up laying down their lives for the Lord Jesus Christ.

Another factor that slowed the advancement of Evangelical Christianity in Shandong was brought about by a change of strategy by the Roman Catholics in the province. For decades the Protestants and Catholics had largely left one another alone, but in the 1890s many Evangelicals found that the Catholics were attempting to steal their converts away. The problem was so acute in places that scholars Nevius and Muirhead felt compelled to write books to educate Chinese church members about the differences between the two creeds.

A New Danger Emerges

By God's grace, however, the Body of Christ in Shandong persevered and faithfully endured many hardships. By the end of the nineteenth century—after four decades of labor— the Evangelical churches throughout the province had grown to contain 13,500 members, spread among nine different denominations and mission societies. 14 Among the teeming millions of people crammed into the province, the Body of Christ was like a little flock of sheep, but little did they know that their faith was about to be tested by ferocious persecution.

In the later part of the decade a subgroup of the White Lotus Society in Shandong Province came to be known as the ‘Boxers.’ They launched the notorious Boxer Rebellion in 1900, resulting in the slaughter of thousands of Christians throughout China.

© This article is an extract from Paul Hattaway's book 'Shandong: The Revival Province'. You can order this or any of The China Chronicles books and e-books from our online bookstore.

3. Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (November 1885), p. 434.

4. Miss Fosbery, "The Story of a Chinese Boy," China's Millions (March 1886), pp. 34-5.

5. Mr. Judd, "Baptisms at Ning-Hai, Shan-tung," China's Millions (September 1888), p. 114.

6. Mrs. Judd, "To the Poor the Gospel is Preached," China's Millions (May 1889), p. 62.

7. Barr, To China with Love, p. 93.

8. Barr, To China with Love, p. 43.

9. Cliff, A History of the Protestant Movement in Shandong Province, pp. 204-5.

10. A.G. Jones, "The Poverty of Shantung, Its Causes and Treatment," Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (April 1894), pp. 182-3.

11. Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (May 1891), p. 234.

12. Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (December 1890), pp. 578-9.

13. Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal (November 1892), p. 542.14. Cliff, "Building the Protestant Church in Shandong," p. 64.